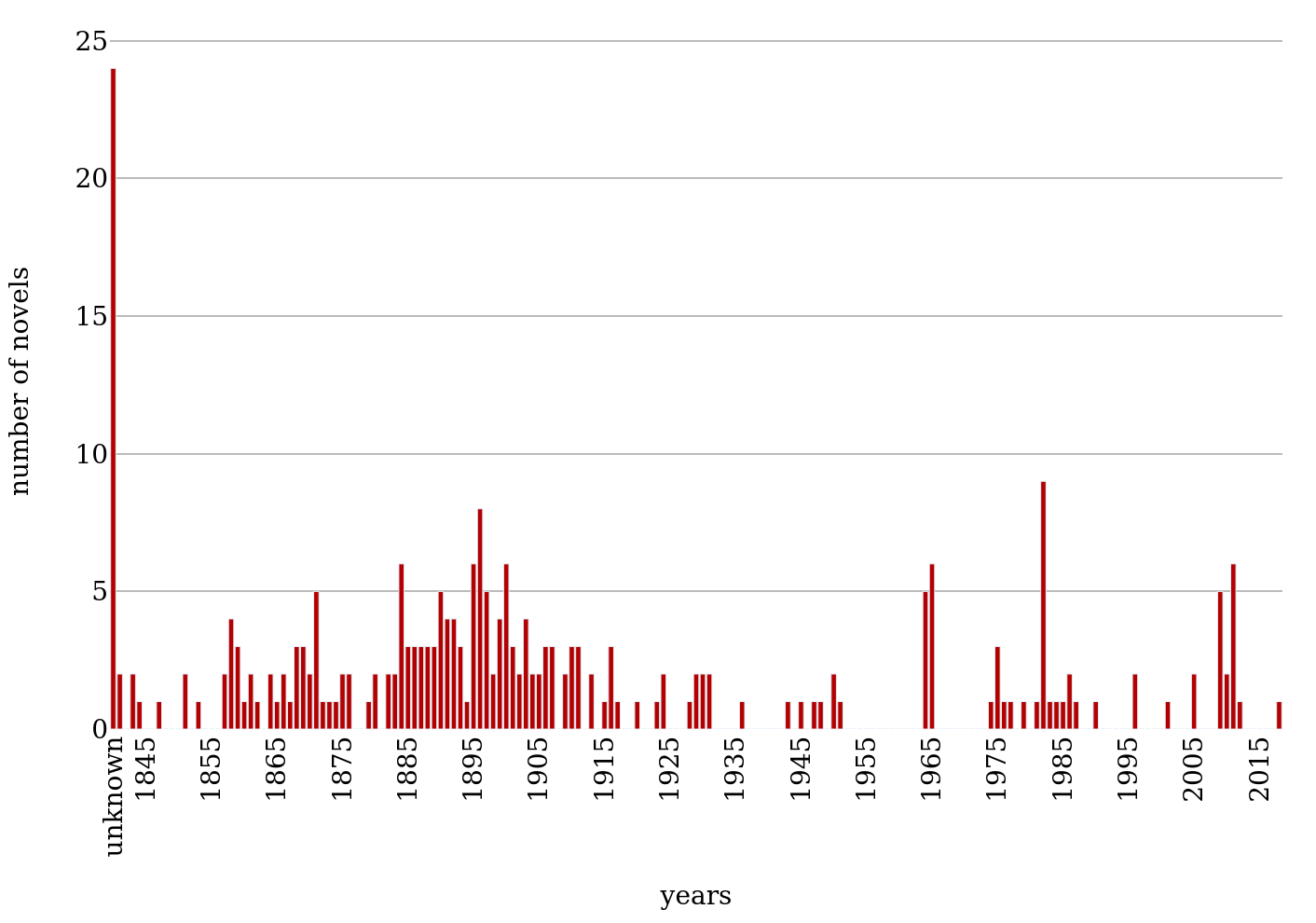

167The corpus used for the analysis of subgenres in this dissertation is presented in this chapter. Besides the text corpus itself, a bibliographical database of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels was created. On the one hand, it had the purpose of serving as an information pool from which to retrieve data about authors, works, and editions during the process of corpus creation. On the other hand, it approximates the population from which the actual text corpus was sampled so that eventual particularities of the corpus can be assessed. Furthermore, the digital bibliography and corpus, which were created in the context of this thesis, constitute general databases for digital text or metadata analysis on nineteenth-century novels from Argentina, Cuba, and Mexico. In this chapter, all the aspects of these two resources that are relevant for their use in digital genre analysis are presented so as to provide a thorough documentation of both databases and to encourage reuse, even if not every aspect of the metadata and text encoding is used in the text analysis part of this dissertation.

168The chapter is organized as follows: In chapter 3.1, the criteria used for the selection of texts for the bibliography and the corpus are discussed. The creation of the bibliographical database and the corpus itself – their sources, data model, text treatment, metadata, and text encoding – are outlined in chapters 3.2 and 3.3. Overviews of the contents in the bibliography and the corpus are given in the chapter following this one: In chapter 4.1, the authors, works, editions and subgenres contained in both resources are analyzed and compared regarding their distribution by selected metadata and text parameters (for instance, by country and time period). At some points, the discussion of the selection criteria in chapter 3.1 already refers to digital bibliographical information and full texts as bases for decision-making because the processes of defining the selection criteria and building the databases went hand in hand: an initially broad data basis was analyzed and successively cut to satisfy stricter criteria.

169Unless otherwise stated, the selection criteria that are discussed in this subchapter apply both to the bibliographical database and to the text corpus. As the subject of this study are subgenres of the novel, a definition of the novel itself as the higher-level genre is necessary to be able to select the texts. Texts of all kinds of subgenres are included, even though the analysis focuses on some of them: determining the subgenres is a topic in itself and the corpus serves as a background foil for individual subgenres. The boundaries of the novel are discussed in chapter 3.1.1. Although this dissertation aims to analyze subgenres of Spanish-American novels, not all of the countries belonging to the region are taken into account simply because it would be too challenging to regard all the individual literary-historical contexts of the new nations and old colonies. Instead, it was decided to concentrate on three countries: Mexico, Cuba, and Argentina. In chapter 3.1.2, it is explained why these three countries were chosen and how it was decided which novels are associated with each of them. Chapter 3.1.3 explains which limits of the nineteenth century were used here to select the texts.

170To facilitate an understanding of the examples, also in the cases of lesser-known works, whenever individual works are mentioned, the year of their first publication and a country code is given in parentheses after the title. For all the selection criteria, it was an objective to find ways to decide that are suitable for a quantitative study, in that the amount of necessary close reading of the texts is kept as low as possible, with the goal to make the selection criteria in principle applicable to a corpus of any size.

171The bibliography and corpus are intended to include literary texts that belong to the genre novela. In general, a novel can be defined as a longer fictional narration in prose that is usually published as one or sometimes several independent books (Fludernik 2009, 627Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.; Steinecke 2007, 317Steinecke, Hartmut. 2007. “Roman.” In Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft, edited by Klaus Weimar, Harald Fricke, and Jan-Dirk Müller, 317–323. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.). Besides the general characteristics of the form, manifestations of the novel are very varied, for example, regarding the content of the texts and the kinds of characters or elements of the plot. Most of the criteria that go beyond the broad formal characterization of the genre are only valid for one or several subgenres, excluding others.113 Because no subgenres or types of novels are excluded here from the outset, the general definition of the novel is followed. However, even the above-mentioned formal elements need to be clarified further because they depend on the cultural and historical context under consideration.114 In the following, the individual elements of the above definition of the novel (fictionality, narrativity, prose, length, independent publication) are discussed for the Spanish-American context in the nineteenth century. The methods used to assess these properties for the texts in question are outlined, with a special focus on borderline cases, in order to exemplify where the boundaries of the novel were drawn. Finally, additional criteria complementing the formal aspects are explained, and the various factors are summarized in a working definition of the novel.

172In a pretheoretical understanding, fictionality describes the property of a text (or other medium) to involve fiction, which means that it is about something imagined and invented. A novel, for example, is about events that did not actually take place, even if the author was inspired by the reality he or she knows and even if the author alludes to this reality in the text. Even so, theoretical considerations of fictionality show that it is not enough to assume that a text is fictional if it is about imaginary worlds (Klauk and Köppe 2014, 3Klauk, Tobias, and Tilmann Köppe. 2014. “Bausteine einer Theorie der Fiktionalität.” In Fiktionalität. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch, edited by Tobias Klauk and Tilmann Köppe, 3–31. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.).115 Recent approaches focus on pragmatic aspects to determine the fictionality of a text. According to the “institutional” theory of fictionality, for example, certain texts are considered fictional because of a coordinated and conventional social practice (an institution). A text is produced with the intention to be received according to the conventions of the fictionality institution. The sender and recipient of a fictional text enter into a contract establishing that questions of empirical referentiality and truth are not posed within the confines of the fictional text. The reader accepts the existence of the entities presupposed in the text and engages with them imaginatively if he or she recognizes the intention of the author to write a fictional text. For this, the authorial intention needs to be manifest in the text in some way, but ultimately, it is a pragmatic attribution to determine the fictional intention of a text (Köppe 2014, 35Köppe, Tilmann. 2014. “Die Institution Fiktionalität.” In Fiktionalität. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch, edited by Tobias Klauk and Tilmann Köppe, 35–49. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.; Weidacher 2017, 378–381Weidacher, Georg. 2017. “Fiktionalität und Fiktionalitätssignale.” In Handbuch Sprache in der Literatur, edited by Anne Betten, Ulla Fix, and Berbeli Wanning, 373–390. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.).

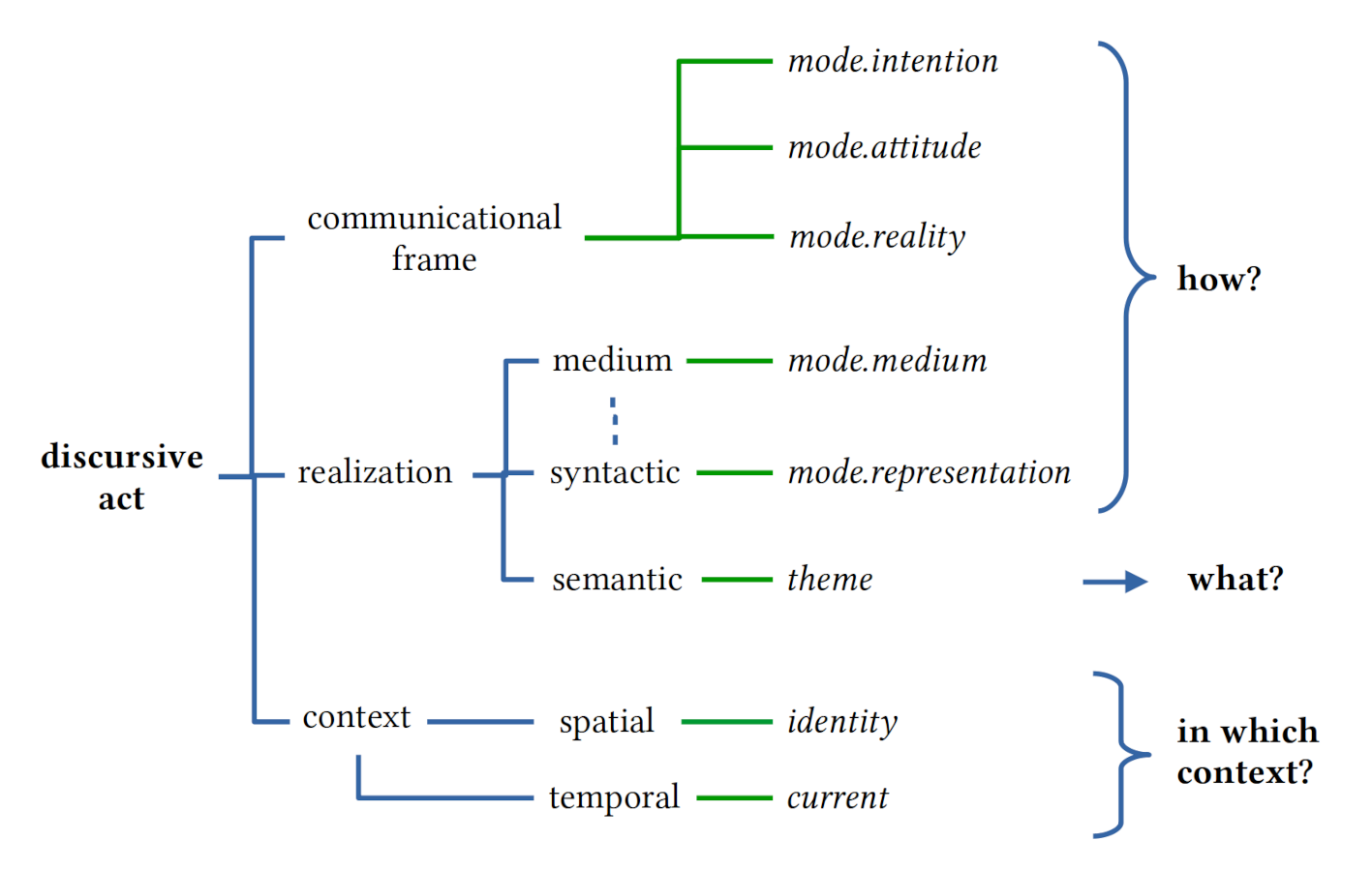

173In accordance with this view, the fictionality of the texts to be included in the bibliography and the text corpus was assessed as follows. Statements of authors and readers regarding the fictionality of a text were taken into account. If it was indicated clearly that the text was conceived and received as fictional at the time and place of its publication, these signals were highly rated. In addition to explicit statements concerning the fictionality of the text, other paratextual and textual signals were evaluated. A comprehensive overview of potential signals of fictionality is given by Zipfel (Zipfel 2014, 97–119Zipfel, Frank. 2014. “Fiktionalitätssignale.” In Fiktionalität. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch, edited by Tobias Klauk and Tilmann Köppe, 97–124. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.), who organizes them as follows:

174Of the various potential signals of fictionality, peritextual signals were especially useful to evaluate whether texts are to be considered fictional and if they should become part of the bibliography and the text corpus because they are very accessible.116 Details such as author, title and subtitle, place of publication, publisher, and series are usually included in bibliographic descriptions of work editions and can, therefore, also be taken into account when the texts themselves are not available.117 A good indicator is a genre label in the title or subtitle of a work that refers to a fictional text type. Examples of such titles for Spanish-American narrative texts in the nineteenth century are: “novela”, “relato”, “narración”, “leyenda”, “romance”, “cuento”, or “drama”. There are other labels that are also common but less clear regarding the fictional status of the texts, for example: “historia”, “crónica”, “estudio”, “esbozo”, “cuadro”, “escenas”, “episodio”, “memorias”, “apuntamientos”, “anécdotas”. Sometimes labels refer to subgenres, such as “aventuras” or “costumbres”. To be able to decide whether a text is to be considered fictional or not in cases where labels are ambiguous, or where there are no explicit labels at all, other kinds of information were used. Where editions of a work were accessible, prefaces, introductions, and headings were consulted to see whether they clear up the issue of fictionality. Textual signals on the level of the story and on the level of the narration were also taken into account, but only in cases of doubt. A textual signal that is easy to recognize typographically and is typical for fictional narrative texts, though it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient criterion, is the reproduction of direct speech. Words or phrases that mark the end of a story or text can also be easily identified. Epitextual signals were not systematically researched. Especially for the bibliographical database, decisions were also based on information from existing bibliographies of fictional texts, literary histories, and other critical research literature.

175In the case of Spanish-American novels, there are several factual text types that share characteristics with certain subtypes of the novel in terms of content or narrative mode. These are historiographic works versus historical novels, (auto)biographies versus (auto)biographical novels, travelogues versus travel novels, philosophical treatises versus philosophical novels, political treatises versus political novels, etc. That the boundaries between some kinds of fictional and factual texts are not always clear is influenced by several factors. Many of the authors in the nineteenth century who wrote novels were also authors of historiographic, political, journalistic, or philosophical works because there were still very few professional literary writers. Furthermore, many Spanish-American countries reached their political independence in the early nineteenth century, and there was a need to justify it and to contribute to the creation of a national identity not only through historiography but also by means of literary works (Kohut 2016, 171–172Kohut, Karl. 2016. Kurze Einführung in Theorie und Geschichte der lateinamerikanischen Literatur (1492–1920). Berlin: Lit Verlag.; Lindstrom 2004, 76–77Lindstrom, Naomi. 2004. Early Spanish American Narrative. Austin: University of Texas Press.; Sommer 1993Sommer, Doris. 1993. Foundational Fictions. The National Romances of Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.). In his essay “Revistas literarias de México” from 1868, the Mexican author Ignacio Manuel Altamirano explains the ever more important role of the novel in this process:

La novela es indudablemente la producción literaria que se ve con más gusto por el público, y cuya lectura se hace hoy más popular. Pudiérase decir que es el género de literatura más cultivado en el siglo XIX y el artificio con que los hombres pensadores de nuestra época han logrado hacer descender a las masas doctrinas y opiniones que de otro modo habría sido difícil que aceptasen. [...] la novela hoy ocupa un rango superior, y aunque revestida con las galas y atractivos de la fantasía, es necesario no confundirla con la leyenda antigua, es necesario apartar sus disfrazes y buscar en el fondo de ella el hecho histórico, el estudio moral, la doctrina política, el estudio social, la predicación de un partido o de una secta religiosa: en fin, una intención profundamente filosófica y trascendental en las sociedades modernas (Altamirano 1868, 17–18Altamirano, Ignacio Manuel. 1868. Revistas literarias de México. México: T. F. Neve.)

176As long as they are either designated directly or indirectly as fictional in their paratexts or exhibit characteristics that are typical for fictional texts, these works were included in the bibliography and the corpus, even if they resemble factual texts because of their content or because of the way the narration is organized.

177For example, the Mexican author Ireneo Paz wrote several historical novels that he labeled as such, but also a series of “leyendas históricas”. They are all centered on historical figures, as their titles suggest: “El Lic. Verdad”, “La Corregidora”, “Hidalgo”, “Morelos”, “Mina”, “Guerrero”, “Antonio Rojas”, “Manuel Lozada”, “Su Alteza Serenísima”, “Maximiliano”, “¡Juárez!”, “Porfirio Díaz”, and “Madero” (Pi-Suñer Llorens 2005, 386Pi-Suñer Llorens, Antonia. 2005. “Entre la historia y la novela. Ireneo Paz.” In La república de las letras. Asomos a la cultura escrita del México decimonónico, edited by Belem Clark de Lara and Elisa Speckman Guerra, 379–392. Vol. 3: Galería de escritores. México: UNAM.). They could also be interpreted as historical biographies, but because they are labeled as “legends” and contain direct speech, detailed descriptions of situations (e.g., weather conditions) and characters (e.g., behavior and appearance in specific situations), they are considered fictional texts here.

178A work that is sometimes mentioned in critical works on the Spanish-American novel is “Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga” (1845, AR) by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.118 In the first part of the work, the country, its inhabitants and their customs are described, followed by a biography of the Argentine caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga. The last part contains considerations about Argentina’s political and economic future (Lichtblau 1959, 39–40Lichtblau, Myron I. 1959. The Argentine Novel in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States.). In a preface, the author refers to reactions by readers who missed certain details in the descriptions of historical events. Sarmiento defends himself by explaining how difficult the coordination of events that occurred in so many different places and at so many different points in time was challenging with the limited means he had (some reports of eyewitnesses, some simple manuscripts, some aspects recalled from his memory). He ends with the intention to improve his work in these aspects if time allows:

Quizá haya un momento en que, desembarazado de las preocupaciones que han precipitado la redacción de esta obrita, vuelva a refundirla en un plan nuevo, desnudándola de toda digresión accidental, y apoyándola en numerosos documentos oficiales, a que sólo hago ahora una ligera referencia. (Sarmiento [1845] 2000, sec. Advertencia del autorSarmiento, Domingo Faustino. (1845) 2000. Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga (en formato HTML). Edited by Benito Varela Jácome. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmc18359.)

179In this authorial statement, there cannot be recognized any intention to write a fictional text. Moreover, the different parts of the work are not unified, and there are very few passages where direct speech is reported. “Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga” is therefore considered a non-fictional text and excluded from the bibliography and the corpus.

180Other borderline cases are descriptions of travels, for example, “La tierra natal” (1889, AR) by Juana Manuela Gorriti, “Mis montañas” (1893, AR) by Joaquín Víctor González, and “Una excursión a los indios ranqueles” (1870, AR) by Lucio Victorio Mansilla. All three texts also include autobiographical elements. For a factual travel narrative, three conceptual aspects are essential:

181When the three examples are examined, the following characteristics can be determined. In “La tierra natal”, the framing story is a railway trip from Buenos Aires to Salta. The text is structured into chapters that roughly correspond to stops of the journey. The traveler and first-person narrator gives an account of the journey and inserts conversations of fellow passengers, but also memories of her hometown. In a preface, Gorriti calls her work “páginas de lejanas memorias” (Gorriti [1889] 2001, 1Gorriti, Juana Manuela. (1889) 2001. La tierra natal (en formato HTML). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmc222t4.). The end of the narration is marked with the word “Fin”.

182In “Mis montañas”, the first-person narrator gives a report of a trip to the Sierra de Velazco in the Argentine province of La Rioja. The text is divided into 21 chapters which consist of landscape descriptions and impressions, historical background information and the imagination of historical events, the portrayal of local customs, the evocation of local characters and episodes, and personal memories. The work is prefaced by the Argentine writer Rafael Obligado, who gives several intertextual references. For example, he compares “Mis montañas” to the epic poem “La cautiva” by Esteban Echeverría. However, he does so not to stress its fictionality but the literary treatment of the Argentine landscape: “La propiedad artística de la cordillera argentina pertenece a Vd. de hoy para siempre, como la de la llanura al poeta de La Cautiva” (González [1905] 2001, XGonzález, Joaquín Víctor. (1905) 2001. Mis montañas (en formato HTML). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmcw37r4.).119

183“Una excursión a los indios ranqueles” begins with a letter written by the narrator, identified as “Lucio” and “coronel Mansilla”, just like the author, to his friend Santiago, in which he explains the circumstances of his expedition to the province of Córdoba where the indios ranqueles live. In 68 chapters, the narrator recounts his experiences in the form of letters to his friend. The work contains descriptive passages concerned with sociological, zoological, botanic, philological, and folkloristic facts, but also an intercalated novella and novelistic amatory and military scenes (García 1952, 132García, Germán. 1952. La novela argentina: Un itinerario. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana.; cited by Lichtblau 1997, 609Lichtblau, Myron. 1997. The Argentine novel: an annotated bibliography. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.; Rössner 2007, 186–187Rössner, Michael. 2007. Lateinamerikanische Literaturgeschichte. 3rd ed. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.).

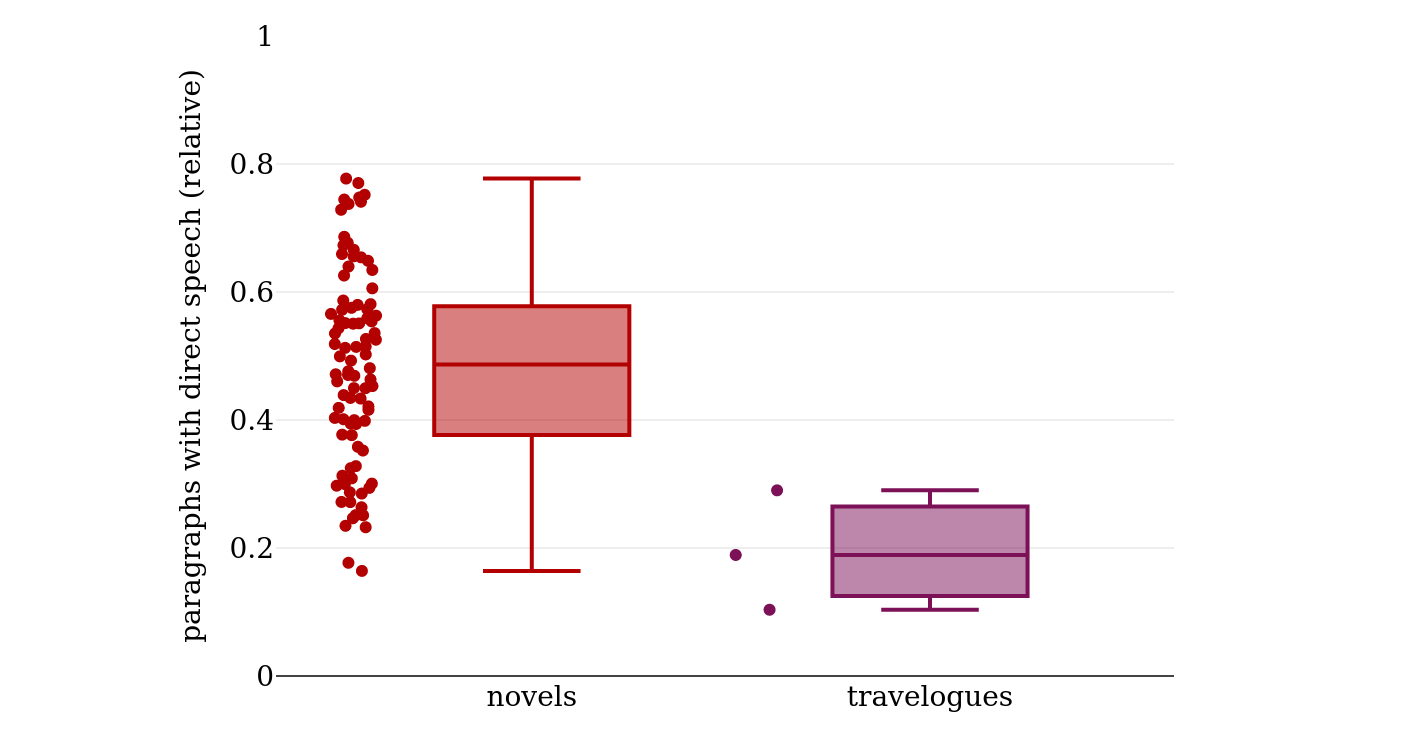

184In all three works, the discourse is organized around a

journey that actually took place. All the texts are narrated in the first

person, and the narrator can be identified with the author, either because

of an explicit mention in the text (“Una excursión a los indios ranqueles”)

or because of implicit formulations in the prefaces (“La tierra natal” and

“Mis montañas”). In the paratexts, there is no clear evidence that the three

travelogues were conceived or perceived as fictional. As to the third

defining aspect of a factual travel narrative, the nature of the three works

under consideration is less clear. All of them combine descriptive with

narrative passages and objective representations with subjective perceptions

to different degrees. One indicator for a narrative style, and hence a

fictional text, that can be evaluated quantitatively is the amount of direct

speech in the three texts. In figure

2, the travelogues are compared to other novels in the corpus

regarding the proportion of paragraphs containing direct speech.120 As can be seen, the amount

of direct speech in the three travelogues is less than in 75 % of the

novels, so even if there are novels with an equal proportion of paragraphs

containing direct speech, they do not represent the typical novel.

185To conclude, even though the three travelogues resemble novels in some aspects (narrative, subjective, and probably also fictional passages), they also share essential characteristics with factual travel narratives, and there are no indications that they were intended and read as fictional texts in their time. As a consequence, they were excluded from the bibliography and the corpus, even though they exhibit a certain generic ambiguity.121

186In contrast to the examples that were discussed in detail above, in the majority of cases, the fictional status of the texts that were candidates for the bibliography and the text corpus could be determined easily based on paratextual information, bibliographical and literary-historical sources. In the unclear cases, a reasoned decision was made, as exemplified above, whereby textual and paratextual information was preferred over critical discussions as far as possible.

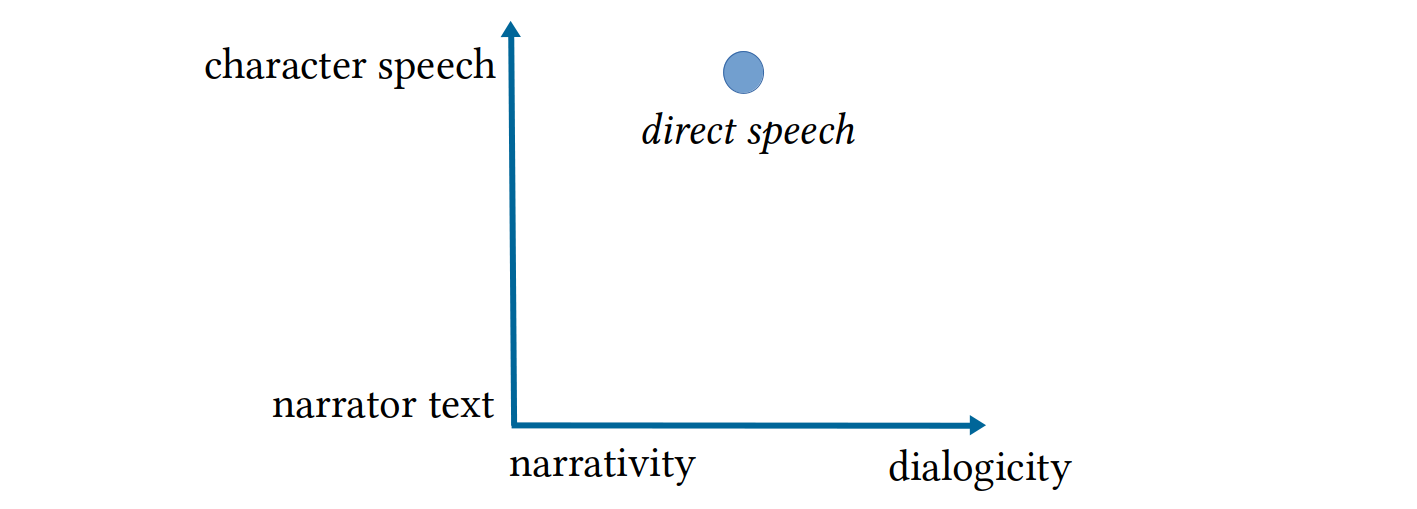

187According to Weber, narration is “[1] adressierte, [2] serielle, [3] entfaltete berichtende Rede [4] mit zwei Orientierungszentren [5] über nicht-aktuelle (meist: vergangene), [2] zeitlich bestimmte Sachverhalte (besonders: Ereignisse in zeitlicher Folge) [6] von seiten eines Außenstehenden” (Weber 1998, 63Weber, Dietrich. 1998. Erzählliteratur. Schriftwerk, Kunstwerk, Erzählwerk. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.; cited by Zymner 2017, 365Zymner, Rüdiger. 2017. “Narrative Gattungen.” In Grundthemen der Literaturwissenschaft: Erzählen, edited by Martin Huber and Wolf Schmid, 365–383. Berlin: De Gruyter.).122 The various elements of this definition will be briefly explained here. While Weber’s definition also holds for oral narration, it will only be applied to written narration in this context.

188Although this definition was very useful for the decision to include texts into or exclude them from the corpus, provided that they were, in principle, available, its usefulness for the selection of entries for the bibliography was limited in the same way as for fictionality. Where editions of the texts could not be accessed, it was necessary to rely only on available metadata and on third-party information. In terms of metadata, mentions of narrative genres in book titles and subtitles or in titles of book series were especially helpful. Regarding third-party information, it had to be taken into account how narrativity was defined in each context (if it was defined at all). For example, Lichtblau discusses the selection criteria for his bibliography as follows:

The problem of identifying those works that clearly belong in the classification ‘novela argentina’ beset me at every stage in the preparation of this bibliography. But I have attempted, within a certain arbitraryness inherent in all literary categorization, to be consistent in the selection or omission of the works cited. [...] In addition, I have included a few celebrated works of Argentina literature that, although not novels, retain many of the characteristics of that genre and are associated with its development and artistic expression. We may thus say that Echeverría’s El matadero, Cané’s Juvenilia, and Mansilla’s Una excursión a los indios ranqueles have been recruited for this bibliography without having the proper credentials as ‘novel’. I did leave out, however, Sarmiento’s Facundo, not wishing to stretch the point too much. (Lichtblau 1997, XV–XVILichtblau, Myron. 1997. The Argentine novel: an annotated bibliography. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.)

189He does not provide an explicit definition of the novel and does not refer to the concept of narrativity. His criteria could only be inferred from the examples that he mentions.123 Therefore, wherever full texts were available, the information obtained from other bibliographies was checked before a work was included in the current bibliography. An example of a text that is included in Lichtblau’s bibliography (Lichtblau 1997, 309Lichtblau, Myron. 1997. The Argentine novel: an annotated bibliography. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.), but excluded here, is “La flor de las tumbas” (1866, AR), written by Santiago Estrada because the text has the form of a dramatic text instead of a narrative text. It starts with a cast list, is divided into acts and scenes, contains stage directions, and consists entirely of character speech. This does not fulfill the criteria established by Weber, especially that a narration should be addressed, reported by someone external, not be immediate, and have two centers of orientation. In the preface, the author explains how he conceived his work generically:

Este trabajo no es un drama en la acepción literaria de la palabra. Moriría en el teatro, para el cual no está dedicado. El artista puede revestir sus concepciones en la forma que mejor se avenga a su expresión espontánea.—Este trabajo es un romance. Dibujar los cuadros o pintarlos, eso queda al arbitrio del artista. ¿Quién me obligaría a prestarle el empaste de la narración?

¿Puedo esperar que una lágrima escapada del alma del lector, le de el colorido que yo le niego, dejándolo en la simplicidad elemental de sus líneas?... No lo sé.—Escribo para sentir, y nada más.

Su forma no carece de precedentes. Sin traer a recuerdo magistrales producciones literarias, que tomando la división y sencillez del drama, no han aspirado a la exhibición viva de la escena, citaré solamente los conocidos romances que un poeta francés ha llamado: comedias de sillón,—y las que el marqués de Varennes ha denominado: proverbios.

Esto por lo que respecta a la forma.

(Estrada 1866, 5Estrada, Santiago. 1866. La flor de las tumbas. Buenos Aires: Imprenta del Siglo.)

190Estrada thus says that his work is not a drama because it is not intended to be presented on stage. Instead, he calls it “romance”. However, he also clearly says that it does not have the form of a narration. It is kept “simple” and “rudimentary”, without coloring, drawn, but not painted, which a narration in the sense of a detailed, stylistically evolved report would be.

191In general, however, it was easier to determine the narrativity of the texts eligible for the bibliography and the text corpus than their fictionality. As to the borderline cases for fictionality, the historical biographies and the travelogues are, for the most part, narrative. Only Sarmiento’s “Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga” is not predominantly narrative, but it would still have to be discussed how much narrativity a text needs in order to be interpreted as a narration. As Weber states, when he elaborates his definition further, normally, a narration does not consist entirely of narrative text. It can also contain other forms of presentation, for example, the report of direct speech, descriptions, argumentative passages, or comments (Weber 1998, 64–70Weber, Dietrich. 1998. Erzählliteratur. Schriftwerk, Kunstwerk, Erzählwerk. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.). An example of a text containing scenic presentation is the historical novel “La loca de la guardia” (1896, AR), written by Vicente Fidel López. In chapter 40, the conversation between a judge and an accused person in a trial has the form of dramatic speech. Nevertheless, this passage amounts only to about 5,300 words, and the entire novel has a length of approximately 97,500 words, so it can still be considered a narrative text.

192“Prose” can be defined as a form of text that is metrically not bound, as opposed to text in verse form (see, for instance, Kleinschmidt 2003, 168Kleinschmidt, Erich. 2003. “Prosa.” In Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft, edited by Klaus Weimar, Harald Fricke, and Jan-Dirk Müller, 168–172. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.). This criterion concerns primarily the distinction between narrative prose and poetry. Many of the Spanish-American novels in the nineteenth century contain inserted poems. They may be quotations at the beginning of individual chapters or part of the narration, for example, if they are recited in public by a character or are part of a love letter that is represented in the text. In general, these insertions only make up a small part of the entire text and do not question that a work is written predominantly in prose. As for the selection of texts for the bibliography, caution is required when works carry the generic label “romance” or “leyenda” because they can either be novels written in prose (for example, “El romance de un médico” (1905, AR) by Cupertino del Campo and “Un santuario en el desierto. Leyenda original” (1890, MX) by José Francisco Sotomayor) or epic texts written in verse (e.g., “Perfiles de la conquista. Romance histórico. 1521–1887” (1887, MX) by Juan Antonio Mateos and “Un ángel desterrado del cielo. Leyenda religiosa” (1855, MX) by Niceto de Zamacois). The latter were excluded from both the bibliography and the corpus.124 There are also many texts without generic labels, which can be of any genre (novels, collections of short stories or poems, plays, other types of literary or non-literary texts) and be written in prose or verse. In these cases, the recourse to existing bibliographies of the novel and to library catalogs that include information about the genre was indispensable to finding the relevant texts.

193The length of the text is one of the criteria that serve to distinguish the novel from other forms of fictional narration in prose, especially shorter ones such as the novella and the short story. However, usually, these genres are also differentiated according to other criteria because there may be exceptions, for example, very short novels and very long novellas, so that a novella might be longer than a novel in individual cases. Moreover, there is no consensus on the exact or approximate lower boundary of the length of a novel. Traditionally, the length of a fictional narration is expressed in page numbers which can only be a rough indicator because of differences in book format, layout, and typography from one edition to another.125 It is more precise to measure the length of a text independently of the design of a print edition, for example, in the number of words or characters, but this is only feasible for texts which are available in electronic form and machine-readable.

194In “Aspects of the novel”, a collection of literary lectures about the English language novel held in 1927, Forster claims: “Any ficticious prose work over 50,000 words will be a novel for the purposes of these lectures” (Forster 1927, 17Forster, E. M. 1927. Aspects of the novel. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.), but without motivating the number. In the context of a German handbook on literary genres, Fludernik mentions the following page limits: She sets an upper limit of 40 to 50 pages for the short story and the novella and a lower limit of 80 pages for the novel, leaving a corridor of about 30 pages for unclear cases (Fludernik 2009, 632Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.). Unfortunately, she also does not explain how she arrives at these numbers. A more detailed discussion about the extension of the short story, novella, and novel can be found in “La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX” by Mata, who is looking for pragmatic criteria allowing him to define the scope of his object of study. He points out that every proposal of an exact number can, at best, apply to a specific historical context but not to the novel in general. As to Forster’s suggestion, Mata states that the number of 50,000 words seems appropriate for the typical, extensive novels of the nineteenth century but not for many of the paradigmatic novels of the twentieth century, which are shorter (Mata 1999, 16Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). It should be added that also the geographical and the cultural context determine the characteristics of a historical genre. In the nineteenth century, the novel had a longer tradition in Europe than in Spanish America and was more stabilized as a genre (Fludernik 2009, 638–645Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.),126 so it can be assumed that more works complied with the established model of the time. The range of the texts considered novels in the nineteenth century in Spanish America was broad. In the early century, many of the novelistic narrative texts in prose were quite short,127 while European models – extensive historical, realist, and naturalistic novels – gained more ground towards the middle and end of the century.128 Towards the turn of the century and in the twentieth century, many novels were shorter again, in correspondence, interrelation, confrontation, and also independence from European developments.129 Using the limit set by Forster, many texts that can be assigned to the genre novela would be excluded from analysis. The strategy followed by Mata is to consult calls for literary competitions to see which limits they pose for the length of texts belonging to different narrative genres. On that basis, he arrives at the following numbers: a maximum of 5,000 words for short stories, a minimum of 5,000 words and a maximum of 35,000 words for short novels, and more than 35,000 words for novels (Mata 1999, 16–17Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). Despite his remark on the historicity of genre lengths, Mata relies on modern literary competitions in order to establish the length of novellas or short novels in the nineteenth century, which he analyses. It can only be speculated why he did not use information about literary competitions in the nineteenth century – maybe because of the scarcity of sources?

195An important question is whether it would be more appropriate to distinguish the novel from other, shorter forms of narrative prose not on the basis of text length but using structural and content-related criteria. Usually, the novel is described as a complex form of narration, while the shorter text types are characterized as simpler, single-stranded forms. According to general definitions, the novella, for example, is said to present an exemplary story with one central event, with a closed structure and only a minor elaboration of the characters’ life. The short story is characterized by a relative unity of place, time, and plot. The latter is usually limited to the representation of single events and has an abrupt ending. The characters tend to be typified. In the novel, in contrast, several parallel storylines and subplots, changes of place and time, and fully elaborated characterizations are more common. These structural and content-related aspects are, of course, also induced by the extent of the form (Fludernik 2009, 632Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.; Strube 1993, 21Strube, Werner. 1993. Analytische Philosophie der Literaturwissenschaft. Untersuchungen zur literaturwissenschaftlichen Definition, Klassifikation, Interpretation und Textbewertung. Paderborn: Schöningh.; Zymner 2017, 371–380Zymner, Rüdiger. 2017. “Narrative Gattungen.” In Grundthemen der Literaturwissenschaft: Erzählen, edited by Martin Huber and Wolf Schmid, 365–383. Berlin: De Gruyter.). Ultimately, the complex interplay of the different factors would have to be taken into account to determine to which genre a narrative prose text belongs because none of the criteria is in itself sufficient. The use of general generic definitions is problematic, though, because they do not take into account the cultural and historical context.

196It is questionable whether the novella, for example, was a common genre in literary production in Spanish America in the nineteenth century at all, and even if it was, it is doubtful whether the above-mentioned characteristics would have applied. While novels and short stories can often be distinguished based on the works’ subtitles (“novela” versus “cuento”)130, there is no distinctive term for short novels in Spanish. They are often called “novela”, as well, and sometimes “novelita” or “novela corta” (Mata 1999, 32–33Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.).131 Many short novels were produced in Argentina, Mexico, and Cuba in the nineteenth century. Some were published independently in book form132, some as part of collections of several shorter narrative texts133 and the majority in journals (Mata 1999, 29Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.; Molina 2011, 58–59Molina, Hebe Beatriz. 2011. Como crecen los hongos. La novela argentina entre 1838 y 1872. Buenos Aires: Teseo.). In his account of the nineteenth-century short novel in Mexico, Mata states that short novels were among the first kind of narrative texts which were published a lot in journals shortly after the country’s independence. He characterizes them as generally not having much literary value and not having been designated with the term “novela corta”, which was practically unknown in the early nineteenth century. Many of the terms that were used in the titles of the texts point to the preliminary character of the works: “pequeña novela”, “esbozo de novela”, “proyecto de novela”, “esquema de novela”, “tentativa de novela”, “ensayo de novela”, “apuntes para una novela”, etc. (Mata 1999, 32–33Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). Mata relates these titles, as well as the fact that many shorter novels were simply called “novela”, to the problem of the missing term for the intermediate narrative genre, which on the other hand, already existed in other languages. According to him, the term “novela corta” only became common in the Iberian Peninsula and Mexico towards the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, an observation which can be confirmed by analyzing the works consulted for the bibliographic database (Mata 1999, 33Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.).134 Towards the end of the century, short novels gained prestige, especially in the context of the Modernismo current (Mata 1999, 143Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). Mata argues that all these texts of intermediate length should be treated as “novelas cortas”, understood as a genre between the short story and the novel, which existed from the early nineteenth century on but has been neglected by literary critics and historians (Mata 1999, 139Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). When defining this short novel in the first chapter of his book, he refers to Walter Pabst’s study “Novellentheorie und Novellendichtung”, an account of the origins of the European novella in Romance languages (Mata 1999, 11–12Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.). From a taxonomic perspective, this may make sense, as all of these narrative texts are of intermediate length, but if genre is understood as an historico-cultural phenomenon, it would have to be analyzed if there is a direct relation between the early “novelitas” and the European novellas at all. Mata’s argument that the early short novels were the protagonist of the initial period of the Mexican (national) narrative (Mata 1999, 141Mata, Óscar. 1999. La novela corta mexicana en el siglo XIX. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.) – in their capacity as first attempts towards the genre “novela”, fostered and popularized by the press – seems more likely. Nevertheless, it would have to be examined in detail to what extent authors, readers, editors, and critics of the time understood the early short novels as representatives of the genre novella. For the later short novels, this link would equally have to be discussed, although there is certainly more awareness for the “novela corta” because the term is used more often. Even so, novels, in general, tended to be shorter again, making it difficult to differentiate between “novela” and “novela corta”.135

197To conclude, the short novel is not easily recognizable as an independent genre with a certain coherence in Argentina, Cuba, and Mexico in the nineteenth century. Furthermore, there are reasons to consider many of the shorter novels as novels, as well.136 Therefore, in this dissertation, neither the lower limits for the novel set by Forster (50,000 words) nor by Mata (35,000 words) are used. Instead, an own limit of words was deduced from bibliographic descriptions of novels, taking into account the extent of the texts in conjunction with historical subgenre labels in order to approximate the minimum and the typical length of a novel for contemporary authors and editors. Of course, not all the novels were labeled as such, but the majority were, which makes it possible to arrive at a better understanding of the extent of the texts belonging to the genre in their time. The term “novela” is understood as designating novels, not novellas, despite exceptional cases where it is clearly used in the latter sense.137 Works with the subtitle “novela corta” or “novelita” were excluded from the calculation.

198In principle, it would have been possible to also use structural and content-related criteria to select texts for the corpus, but this would not have been very efficient because an application of these criteria would have presupposed either access to detailed summaries of the texts or a close-reading of all the texts. To be able to decide upon the inclusion of texts into the bibliography, again, either detailed summaries or the full texts of all eligible works would have had to be accessible, which was not the case. Furthermore, the use of structural and content-related criteria would have presupposed established definitions of the various narrative genres, which, especially for the Spanish-American short novel, are not available. The extent of the text, in contrast, is usually part of bibliographic descriptions of the works and is a piece of information that is easy to access. It is therefore used as a proxy here to distinguish between novels and other shorter types of narrative prose texts.

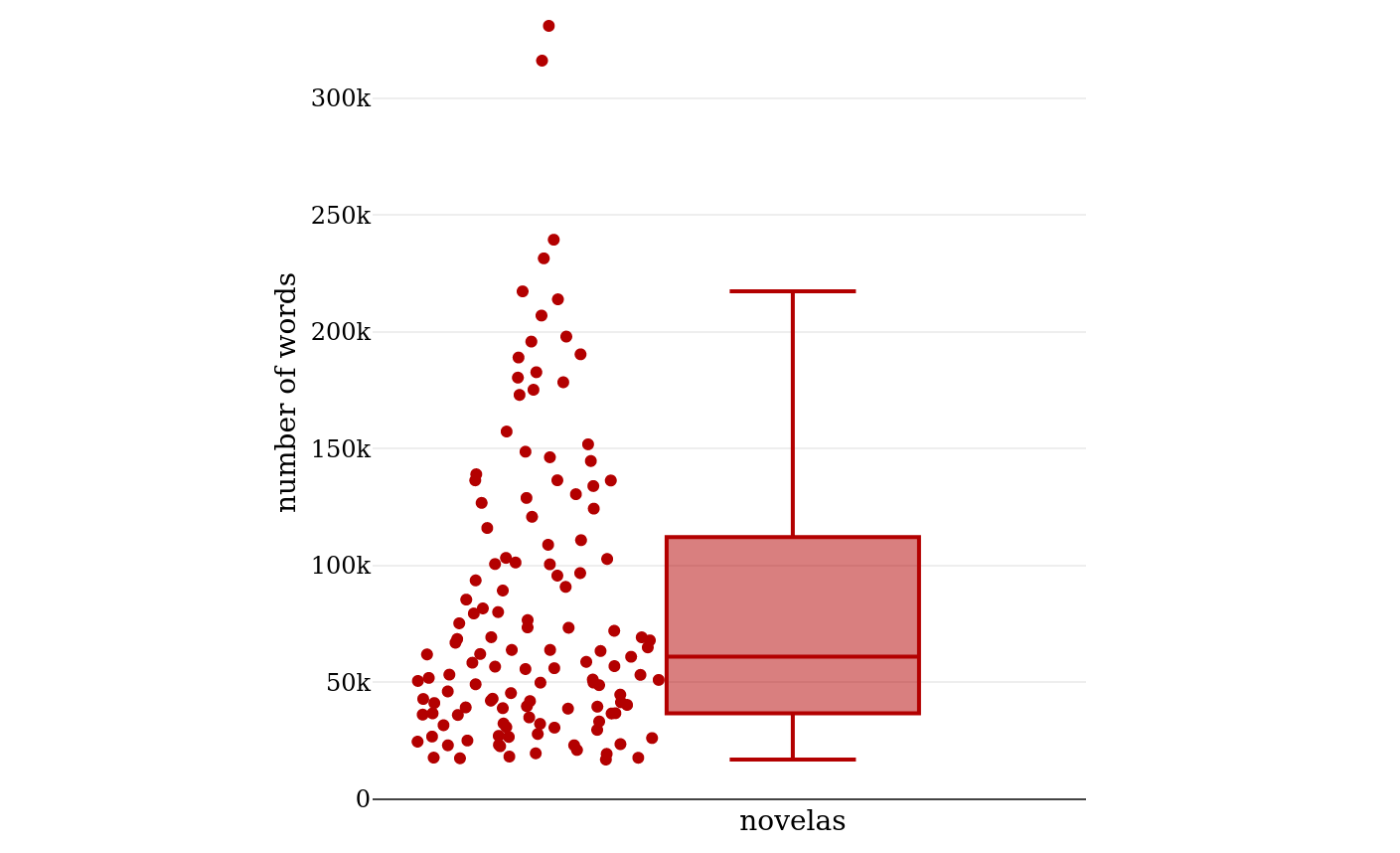

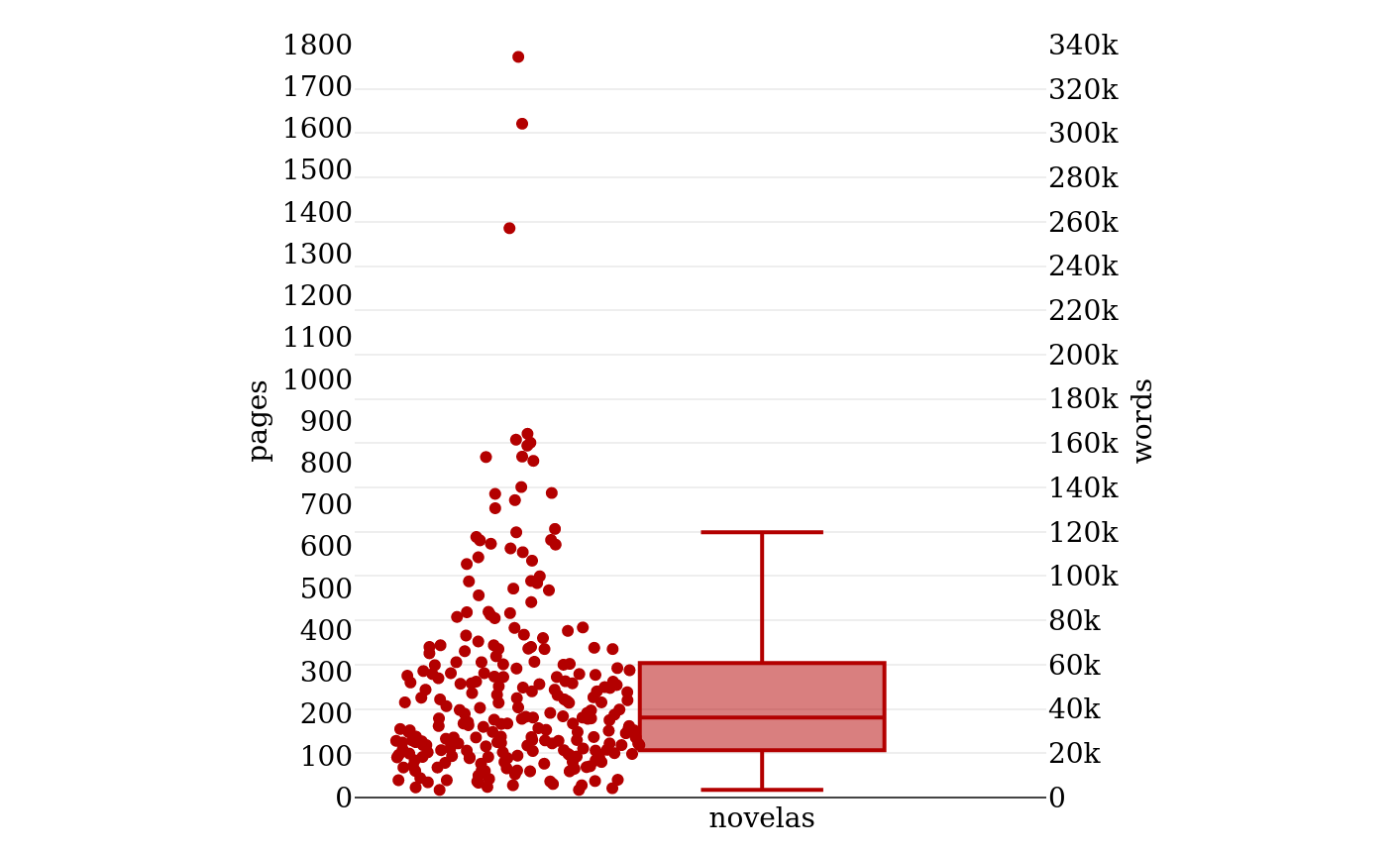

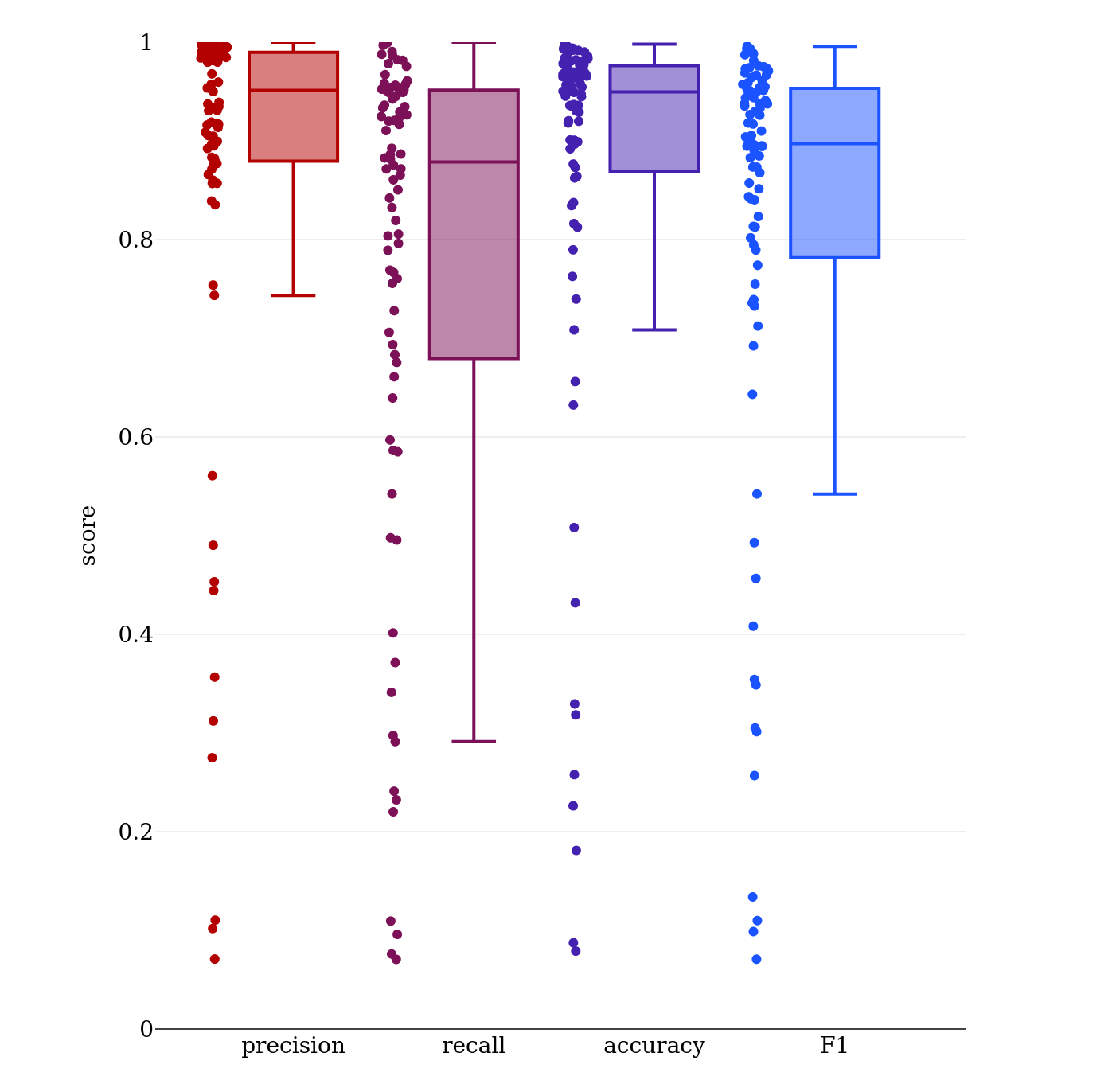

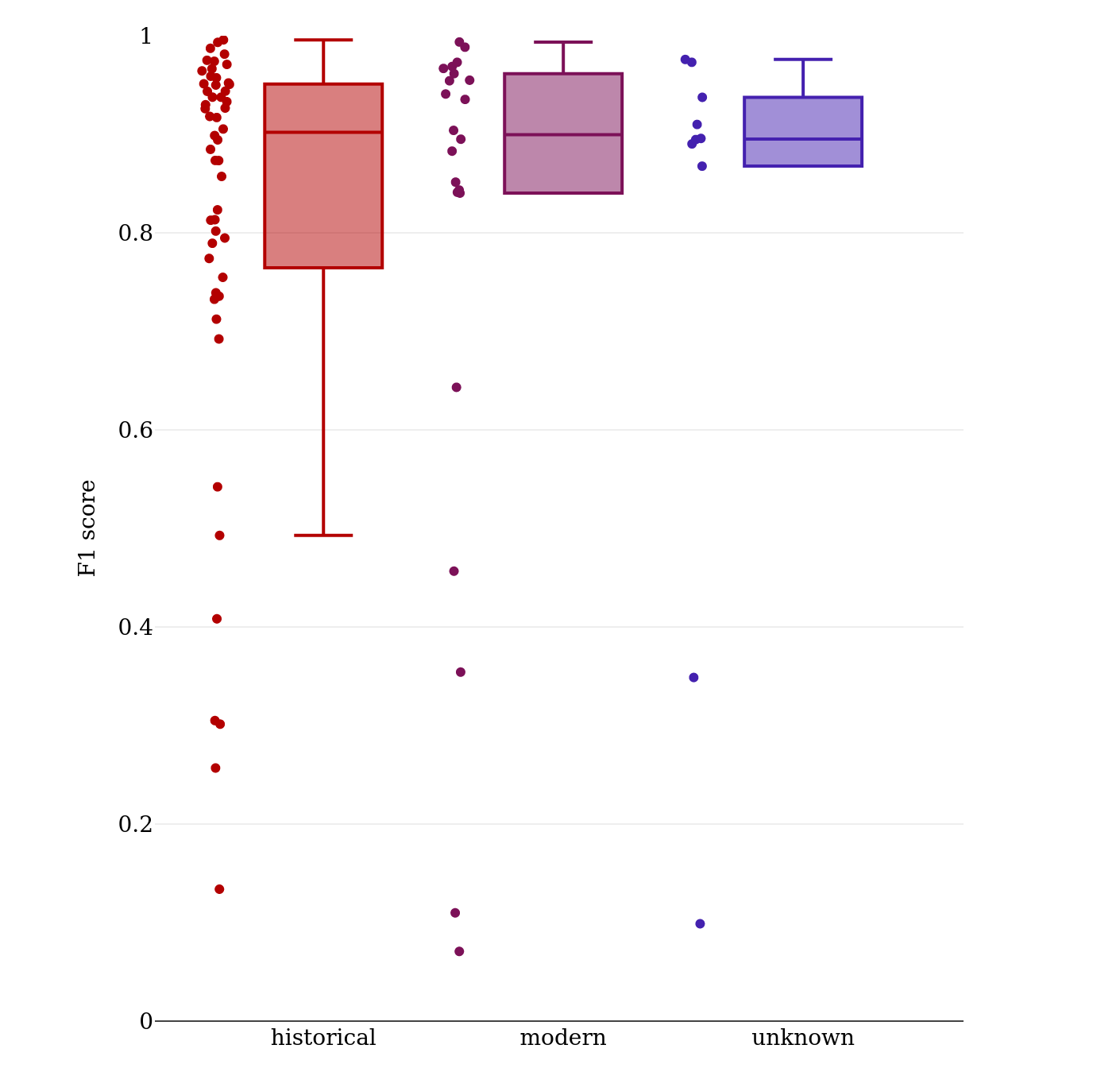

199The unit chosen here to measure the extent of the texts is the

number of words. For each eligible text that is accessible in a full-text

format of good quality,138 this

number was accessed with a simple regular expression counting all the tokens

separated by non-word characters (such as white space or punctuation

marks).139 With this

approach, complex linguistic structures like compounds or words with clitics

are not assessed, but this is acceptable because the focus is on the

comparability of text length and not on the linguistic characteristics of

the texts. For the entries in the bibliography, the number of pages was used

and converted to an estimated number of words. One hundred pages were

selected randomly from 50 different nineteenth-century Spanish-American

novels to identify an average number of words per page and to balance out

differences in layout, typesetting, and font. The words on these pages were

then counted.140

Figure 3 shows the distribution of

the number of words per page for the random sample.141 The number of words per page ranges

from 50 to 475, with a median of 191 words. In the following, this median is

used to estimate the number of words of a text with a known number of pages.

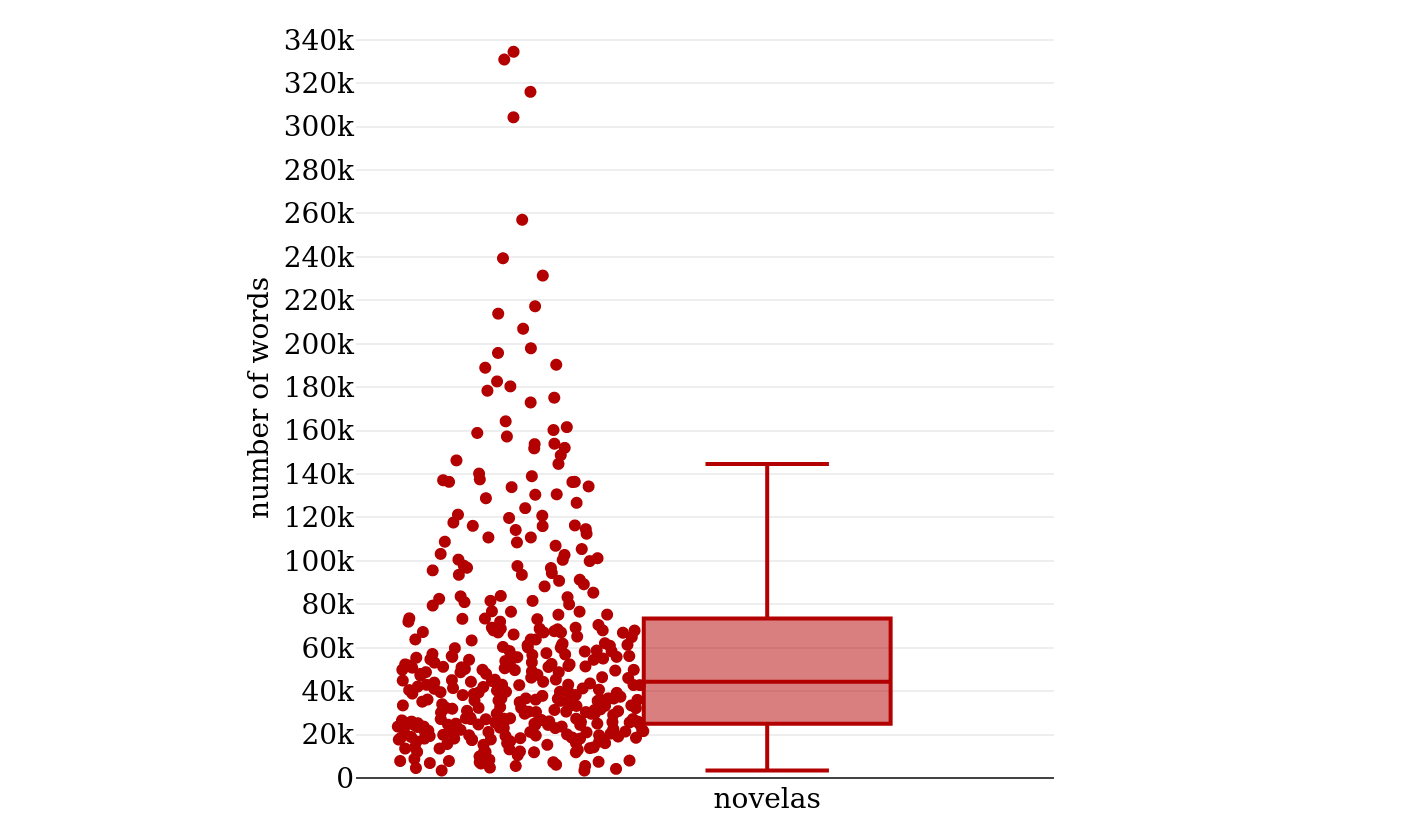

200To examine the range of lengths of nineteenth-century

Spanish-American novels, 129 full texts and 252 bibliographic entries of

works carrying the label “novela” either directly in the title or subtitle

or in the title or subtitle of a series to which the work belongs were

analyzed.142 In the case of the full texts, the words were counted. For

the bibliographic entries, the number of pages was converted to a number of

words using the median number of words per page.143 The results for the

full texts, the bibliographic entries, and both combined are displayed in

figures 4, 5, and 6,

respectively.144 All the distributions have a pyramidal

form which means that they are right-skewed: the higher the number of words,

the fewer works carrying the label “novela” there are, or, in other words,

most of the “novelas” are rather short.145 Looking at the numbers, the

shortest novel in figure 5 has 3,438 words, and the longest one 334,441,

which is almost a hundred times as long, so the spectrum of lengths is very

large. The median is at 44,000 words, the first quartile at 25,000 words,

and the third quartile at 73,000 words.146 With a lower limit of 50,000 words as

proposed by Forster, more than half of the “novelas” would be left out, and

with Mata’s limit of 35,000, still more than one-fourth of them would be

considered short novels.

201Based on these results, the question remained where to make a

cut-off. It did not seem reasonable to include all the texts with the same

length as the shortest “novelas”, as these are only about 20 pages long, so

they clearly overlap with novellas and longer short stories.147 In these cases, a recourse to structural and content-related

criteria would have been indispensable to be able to differentiate between

the genres. It was helpful to look at the length of texts explicitly labeled

as “novela corta” to define a lower word limit. Figure 7 shows the distribution of word lengths of

65 “novelas cortas”.148 Again, the shorter texts dominate, with a few

outliers of greater length. The median for the short novels is around 7,300

words, the first quartile at 4,900, the third quartile at 10,400, and the

upper fence at 16,800 words.149

202Cutting off the “novelas” at the first decile – meaning that the shortest 10 % are left out – leads to a value of 16,000 words as a minimum150, which is very close to the upper fence of the “novelas cortas”. That way, exceptionally long “novelas cortas” are included, while “novelas” of the same length as typical “novelas cortas” are excluded. Reformulated in page numbers, the limit amounts to 84 pages.151 In this dissertation, the word limit was used to select texts for the corpus, and the page limit for the selection of entries for the bibliographic database.152 To be independent of the naming conventions again, all fictional narrative texts in prose of this length were included.

203Of course, this cut-off is still arbitrary to a certain extent – why should a “novela” with 15,000 words or 79 pages be excluded, but a “novela corta” with 16,000 words or 84 pages be included? It is nevertheless a limit deduced on the basis of empirical data from the same cultural-historical context as the works to be analyzed, which makes it probable that it approximates the generic conventions of the time. Furthermore, no clear cut could be seen in the data, the transition from very short to longer novels being rather fluent so that every other limit would have led to a similar arbitrary split. In addition, a numeric criterion is directly usable in a quantitative study without the need for extensive close reading.

204In some definitions of the novel, an independent publication as one or sometimes several books is mentioned as one of the characteristic traits of the texts belonging to the genre (Fludernik 2009, 627Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.; Steinecke 2007, 317Steinecke, Hartmut. 2007. “Roman.” In Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft, edited by Klaus Weimar, Harald Fricke, and Jan-Dirk Müller, 317–323. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.). However, an independent publication will not be required here in order to select texts for the bibliography and the corpus for several reasons. First, the publication of a work as one or several independent books depends to a certain extent on the length of the text. As discussed in the previous subchapter, many of the nineteenth-century Argentine, Cuban, and Mexican novels were quite short and were sometimes published in a volume together with other works, especially when the authors wrote a whole series of novels, for example, the “Entretenimientos literarios” (1843–1844, CU) by Virginia Felicia Auber de Noya or the “Episodios nacionales mexicanos” (1902–1903, MX) by Victoriano Salado Álvarez. Shorter novels were also published in collections of works of various narrative genres, such as the “Panoramas de la vida” (1876, AR) by Juana Manuela Gorriti. Second, the publication in book form corresponds to a particular model of distribution for literary works, which was not the only one in nineteenth-century Spanish America. A large part of the novels was published in journals and literary magazines, many of them in serial form.153 Not all of these novels were also published in book form afterward. Whether a contemporary or modern monographic publication exists also depends on the degree of canonization of a work. As the present study aims to include as many novels as possible so as to broaden the empirical basis for the description and analysis of subgenres of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels, no restrictions are made regarding the form of publication of a work.154

205However, an independent publication in book form is also not just a practical matter related to text length and modes of distribution. Although the question of a novel’s unity and delimitation is not easily answered by requiring it to be published independently, this still emphasizes its autonomy as a work of art. As discussed in the section on length above, very short novels published in book form existed. On the other hand, there are also novelistic works which are so long that they do not fit into one physical volume. These are often published in several books called “tomos”, for example, the first book editions of “El fistol del diablo” (1859–1860, MX) by Manuel Payno with four or “Amalia” (1855, AR) by José Mármol with eight volumes. In the case of sequels and cycles published as several books, it is less obvious if each part should be considered its own novel or if they form one novel altogether. Often, the connection between the texts is indicated in titles and subtitles, as the following examples illustrate:

206In the first case, some aspects point to the unity of the work (that the first volume has the same title as the whole cycle, “Libro extraño”, and that the volumes are called “tomo” like different physical volumes of the same novel in other cases). In contrast, others emphasize the independence of the different parts (that the parts have their own title from the second volume on and that they were all published, and thus probably written and finished, in different years). In the second case, all the parts have a common “supertitle”, “Dramas militares”, they are all published in the same year, and each sequel refers to the previous part(s). Even so, all the parts also have their individual title. In the third case, the title of the first novel does not convey any information about a superordinate work, but the subtitle of the second novel indicates that it is a sequel to the first one. These two works were published in subsequent years. In the last case, all the books are numbered parts of the common superordinate title “Pepa Larrica”, and they were all published in the same year, suggesting a united work. A factor complicating the decision in all of these cases is that none of them includes the label “novela”.

207As a rule of thumb, a work is considered an independent novel here if it has its own title (and optionally a subtitle indicating the genre) that is not a subtitle of a part (such as “Primera parte: El prólogo de un gran libro”, “Segunda parte: La víspera de un gran día”, etc.), if it has its own structure starting with a first chapter and optionally ending with a trailer indicating the end of the work (e.g., “Fin”, “Fin de la obra”), and if it is optionally published in one or several independent books. These parameters are easy to determine not only for texts that are eligible for the corpus but also for bibliographic entries because viewing the table of contents is enough to decide, and no close reading of the full text is needed.158

208Following this rule, the parts of the first three cases above are all considered individual novels, while the fourth case as well as the different parts of a work published in several volumes but all carrying the same title, such as “El fistol del diablo” o “Amalia”, are considered one novel. Thereby, the decision of an author (or editor) to publish a novel with its own title in an independent book is, by and large, respected. The relationship between different parts of a novelistic cycle should, however, not be ignored because it can be expected that there are similarities in content and style that influence the results of an analysis of a whole corpus of novels: it is very probable that these works are closer to each other when compared to other independent works. It can also be assumed that the degree of similarity varies according to the closeness of the parts. The books of “Libro extraño” probably have a stronger stylistic relationship than the different parts of a more extensive and looser series such as the ten novels of “La linterna mágica. Colección de pequeñas novelas / Colección de novelas de costumbres mexicanas” (published between 1871 and 1892, MX) by José Tomás de Cuéllar or the thirteen “Leyendas históricas de la independencia” (published between 1886 and 1913, MX) by Ireneo Paz. The existence of cycles and series of novels with different degrees of connectivity is another factor contributing to the great variance of the genre novel in terms of extent which also a quantitative analysis has to deal with. With the decisions made here, a short novel of around 15,000 words is compared to a novel of several hundreds of thousands of words and both to individual parts of sequels of varying length. If text length is not taken into account in the calculations, several shorter parts of a sequel have more influence on the results than a very long novel considered as one. This must be remembered when analyzing the results of the stylistic analysis.

209Applied to texts not published independently, the rule of thumb leads to the following decisions: a novel published in a journal, possibly in serial form, is considered one work if it has its own title and structure. Such a work is considered finished if all the existent parts are included, and if there is no obvious interruption of the structure.159 Likewise, shorter novels included in collections are treated as individual works if they fulfill the above criteria.160 On the other hand, collections of short stories published independently are excluded because each work contained in them has its own title and, eventually, its own structure.161 Generally, only novels published for the first time between 1830 and 1910 are included.162

210So far, only the very general formal criteria of fictionality, narrativity, prose, length, and form of publication were discussed to select texts for the corpus of novels. Although it is intended not to restrict the definition of the novel much further so as not to exclude texts of certain novelistic subgenres from the beginning, two additional criteria going beyond the form are discussed here. The first one refers to the target readership of the novels. In the bibliography and corpus used in this dissertation, only novels written for adults are included. There are also some novels written especially for children which were published between 1830 and 1910 in the three countries of interest here.163 Although small in number, these are not considered because it is assumed that the target readership influences the writing style, and if they were included, children’s literature would be another influencing factor that would have to be taken into account.

211The second additional criterion is a realistic representation of characters and setting, which has been adduced as an important factor in the definition of the novel in order to distinguish it from epic narrative texts and romances. The latter are characterized by mythical heroes and vague and exotic mythical sceneries (Fludernik 2009, 628–629Fludernik, Monika. 2009. “Roman.” In Handbuch der literarischen Gattungen, edited by Dieter Lamping and Sandra Poppe, 627–645. Stuttgart: Kröner.). This criterion does not necessarily hold for all subtypes of the novel, for example, historical, fantastic, and science fiction novels. Nonetheless, it is helpful to exclude some texts which are very far away from the prototypical realistic novel. In this dissertation, texts with non-realistic elements are included as long as these do not dominate the text and as long as the other selection criteria for novels are fulfilled. Two texts that are sometimes included in bibliographies and representations of the nineteenth-century Spanish-American novel are excluded here: “Peregrinación de Luz del Día o Viaje y aventuras de la Verdad en el Nuevo Mundo” (1871, AR) by Juan Bautista Alberdi and “Los dioses de la Pampa” (1902, AR) by Godofredo Daireaux.164 The protagonist of “Peregrinación de Luz del Día” is the allegorical figure “Verdad” who travels to America to flee from the political and social conditions in Europe. This work has been characterized as a satire, a philosophical dialogue, a novelized allegory, or an allegorical novel (Lichtblau 1997, 16Lichtblau, Myron. 1997. The Argentine novel: an annotated bibliography. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow.; Molina 2011, 403Molina, Hebe Beatriz. 2011. Como crecen los hongos. La novela argentina entre 1838 y 1872. Buenos Aires: Teseo.). It is excluded here because the protagonist is not realistic. In “Los dioses de la Pampa”, Apollo and the Muses travel to Buenos Aires hoping to find the “new Athens”. Disappointed because the arts are disregarded in this big city, they return to Greece. Before leaving, they only catch a glimpse of the Pampa, whose unbeknown, natural gods are presented in the main part of the book and are affiliated with the birth of the Argentine Republic. Because also this text has allegorical traits and, furthermore, no coherent plot, it is excluded, as well.

212If one summarizes the selection criteria outlined in the previous sections, the following working definition of the novel can be set up for the present study:

213A text is considered a novel if:

214This definition of the novel is, on the one hand, general, because some of its elements (fictionality, narrativity, prose, realistic representation) correspond to characteristics mentioned in other general definitions of the novel, as well. On the other hand, it is context-specific because the length and publication criteria were derived from the pool of historical texts considered here. The adult readership criterion is one that is probably not critical in general definitions of the novel but that is included here to avoid stylistic outliers. However, as could be seen in the previous sections, even the general criteria need to be interpreted and broken down into specific paratextual and textual markers in order to be applicable to individual texts in a specific historical and cultural setting.

215This definition is conceived as classificatory, which means that all the conditions should be met by a text to be considered a novel. That way, clear decisions can be made to include texts into a general corpus of novels, which in turn sets the frame for the analysis of subgenres. Inside this classificatorily defined corpus, alternative definitory concepts of (sub)genre(s) are examined.

216This study aims to contribute to the research of subgenres of the novel in Spanish America beyond one specific regional and national context. Therefore, novels from three countries were chosen: Argentina, Cuba, and Mexico. There is a tradition of scholarship concerned with the literature of Latin America or Spanish America as a whole. Usually, “Latin America” includes the countries where the Spanish and Portuguese languages dominate165 while “Spanish America” concentrates on the predominantly Spanish-speaking countries. Several histories of literature and research on the novel exist for these regions.166 However, it can be discussed to what extent it makes sense to speak of “the Spanish-American novel” in the nineteenth century. In general, the literary histories and books on the subject present the nineteenth-century Spanish-American literature (and novel) as a comparison or juxtaposition of the developments in the different countries or regions of neighboring countries such as the Caribbean or Andean countries.167 The differentiated expositions indicate that the common denominator “Spanish-American” is, above all, a retrospective label summarizing individual histories of national or regional literatures and that it does not reflect a coeval self-conception and common literary system. Indeed, literature and especially the novel, had an important function in the consolidation of the nations (Brushwood 1966Brushwood, John S. 1966. Mexico in its Novel. A Nation’s Search for Identity. Austin: University of Texas Press.; Sommer 1993Sommer, Doris. 1993. Foundational Fictions. The National Romances of Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.). It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the advent of the Modernismo current, that the awareness of a common literature evolved clearly:

Zu einem der entscheidenden Merkmale des hispanoamerikanischen Modernismo wird, daß er von Anbeginn ein kontinentales Selbstverständnis entwickelt. Seit den Jahren der Unabhängigkeitskämpfe zu Beginn des 19. Jhs., als Andrés Bello in seinem Londoner Exil mit dem nie vollendeten Gedicht América eine eigene hispanoamerikanische Literatur begründen wollte, hatte es ein solches Selbstverständnis nicht mehr gegeben. Nun trat in Hispanoamerika erneut eine Literatur auf, die beanspruchte, eine Literatur des ganzen Kontinents zu sein. Damit fügte sie sich in ein wachsendes Interesse für Iberoamerika bzw. Lateinamerika, wie es seit der Mitte des Jahrhunderts zunehmend genannt wurde, als Ganzes ein, das die kultur- und geschichtsphilosophische Diskussion des Kontinents bestimmte. (Rössner 2007, 207Rössner, Michael. 2007. Lateinamerikanische Literaturgeschichte. 3rd ed. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.)

217From a comparative perspective, it is nevertheless productive to analyze the subgenres of the novel in several nineteenth-century Spanish-American countries together. Even if there is no shared self-conception of literature throughout the whole century and even if there are no direct historical links in the literary communication and the formation and practice of the subgenres between all the countries and regions, there are still similar historical conditions and indirect connections triggering parallels. As Olea Franco, who examines a series of Spanish-American narrative texts from different countries from the early nineteenth up to the early twentieth century, states: “Creo que mi propia exposición, si bien discontinua, mostrará que en nuestra literatura se produce un diálogo cultural que propicia una unidad de sentido global, tanto en la generación de los textos como en su recepción crítica” (Olea Franco 2011, 25Olea Franco, Rafael. 2011. “Narrativa e identidad hispanoamericanas. De Fernández de Lizardi a Borges.” In La literatura hispanoamericana, edited by Julio Ortega, 23–134. La búsqueda perpetua: lo propio y lo universal de la cultura latinoamericana 3. México: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Dirección General del Acervo Histórico Diplomático.). For Olea Franco, a central aspect of the Spanish-American identity lies in the cultural and, in particular, the linguistic Spanish heritage. Through their language, narrative texts make aesthetic proposals that constitute an implicit or active reflection on cultural identity. In addition, by choosing a topic and a genre for their texts, authors propose in which cultural tradition they expect them to be read (25–26Olea Franco, Rafael. 2011. “Narrativa e identidad hispanoamericanas. De Fernández de Lizardi a Borges.” In La literatura hispanoamericana, edited by Julio Ortega, 23–134. La búsqueda perpetua: lo propio y lo universal de la cultura latinoamericana 3. México: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Dirección General del Acervo Histórico Diplomático.). In the context of the Spanish-American independence movements, the Creole elites had the common task of liberating themselves from the colonial heritage in their search for autonomy. A way to achieve an independent literature was to integrate modes of expression coming from the diverse American realities (28–29Olea Franco, Rafael. 2011. “Narrativa e identidad hispanoamericanas. De Fernández de Lizardi a Borges.” In La literatura hispanoamericana, edited by Julio Ortega, 23–134. La búsqueda perpetua: lo propio y lo universal de la cultura latinoamericana 3. México: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Dirección General del Acervo Histórico Diplomático.).168 The choice of topics and genres also contributed to this goal, for example, the description of regional settings, customs, and types and of local and national (contemporary) historical events in the novelas de costumbres and the novelas históricas, the two subgenres most frequently mentioned explicitly in the subtitles of the novels in the three countries considered here.169 On the other hand, the emerging Spanish-American national literatures all integrated European models (genres, topics, and also stylistic preferences) into their repertoire, so they had similar points of reference, for example, for the romantic sentimental novel, the realist, and naturalistic novels (Cárrega 1986, 49–69Cárrega, Hemilce. 1986. Las novelas argentinas de Carlos María Ocantos. Buenos Aires: Febra Editores.; Navarro 1955, 9–12Navarro, Joaquina. 1955. La novela realista mexicana. México: Compañía General de Ediciones.; Schlickers 2003, 27–51Schlickers, Sabine. 2003. El lado oscuro de la modernización: estudios sobre la novela naturalista hispanoamericana. Madrid, Frankfurt: Iberoamericana/Vervuert.; Varela Jácome [1982] 2000, 12Varela Jácome, Benito. (1982) 2000. Evolución de la novela hispanoamericana en el siglo XIX (en formato HTML). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmct14z8.). So for most of the nineteenth century, the “Spanish-American novel” can be conceived as a frame of a common colonial historical background, similar strategies to develop national novels and related literary influences until a supranational Spanish-American literature begins to emerge. The interest in comparing subgenres of the novels from different countries and regions lies in the possibility to examine the structure of trans-regional similarities and local differences and to analyze it as a pre-phase to a continental literature.

218The countries Argentina, Cuba, and Mexico were chosen because, within the common frame of their colonial heritage, they represent different regions of Spanish America with different geographical and cultural backgrounds and economic, historical, and political developments, which are reflected in the novelistic production, including the different subgenres of the novel. A second reason for the choice of these countries is that their capitals already were or evolved into important cultural centers during the nineteenth century, leading to a great number of novels published there.170 In addition, there were also novels written by Argentine, Cuban, and Mexican writers and published elsewhere.171 In the following, the three countries are characterized briefly regarding historical and socio-economic aspects that had an effect on the number and kinds of novels written in them during the nineteenth century.

219Argentina belonged to the Viceroyalty of Peru until 1776 when the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata was founded, and Buenos Aires became its capital. At that time, Buenos Aires was still a small town but strategically important because of its position at the mouth of the Río de la Plata. However, because of the lack of precious metals, the region was rather neglected and only sparsely settled. The economy remained primarily agrarian during the colonial period. Moreover, the territory belonging to the Río de la Plata region was vast and included extensive rural and unexplored areas such as the Pampa and Patagonia (Lichtblau 1959, 13–21Lichtblau, Myron I. 1959. The Argentine Novel in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States.). The contrast between the backcountry and Buenos Aires, which evolved into a big city and a political, economic, and cultural center in the course of the nineteenth century, influenced the types of novels written by Argentine writers. On the one hand, the economic and social life of the capital was a main topic in many realist and naturalistic novels written towards the end of the century. For example, the role of immigrants in the metropolitan society was discussed because, unlike in many other Spanish-American countries, Argentina’s population was predominantly of a European background. On the other hand, rural life was depicted in gaucho novels (136–184, 19, 121–135Lichtblau, Myron I. 1959. The Argentine Novel in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States.). The nation’s political development was also taken up in the novels. Not long after Argentina’s declaration of independence in 1816 and successive disputes between unitarians and federalists about the organization of the country172, the federalist Juan Manuel de Rosas became the governor of the province of Buenos Aires and established a dictatorial system that persisted until 1852. The Rosas era was the topic in a whole series of novels that depicted its cruelties (Molina 2011, 285–312Molina, Hebe Beatriz. 2011. Como crecen los hongos. La novela argentina entre 1838 y 1872. Buenos Aires: Teseo.; Lichtblau 1959, 15–16 and 43–54Lichtblau, Myron I. 1959. The Argentine Novel in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States.).

220Just like Mexico, during colonial times, Cuba belonged to the viceroyalty of New Spain, which was the first administrative region that Spain established in Latin America and which existed from 1535 to 1821. However, Cuba did not become independent with the end of the viceroyalty. It remained a Spanish colony until 1898 (Kahle 1993, 55, 84–85, 95–96Kahle, Günther. 1993. Lateinamerika Ploetz. Die Geschichte der lateinamerikanischen Länder zum Nachschlagen. 2nd ed. Freiburg/Würzburg: Ploetz.). This makes Cuba a special case because its literature is more closely related to the Spanish literature during the nineteenth century than that of the other independent countries. Depending on the point of view, Cuban-Spanish authors are sometimes claimed to be Spanish authors and sometimes Cuban.173 But even before the existence of a Cuban nation-state, there was a Cuban literature, and it contributed to the emergence of a national identity.174 The capital Havana played an important role in this process. The city was founded by the conquerors in the early sixteenth century and became an important trading post from early on. Important cultural institutions such as the colony’s first printing press and the university of Havana were founded there in the eighteenth century (Armas 1997, 235Armas, Emilio de. 1997. “Cuba. 19th- and 20th-Century Prose and Poetry.” In Encyclopedia of Latin American Literature, edited by Verity Smith, 235–242. London/Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.; Zeuske 2002, 20, 28Zeuske, Michael. 2002. Kleine Geschichte Kubas. 2nd ed. München: C. H. Beck.). For the formation of the novel, private literary gatherings that took place in the houses of habaneros from the early nineteenth century onwards were significant.175 In addition, the Cuban literature was also brought forward by emigrated intellectuals (Armas 1997, 235Armas, Emilio de. 1997. “Cuba. 19th- and 20th-Century Prose and Poetry.” In Encyclopedia of Latin American Literature, edited by Verity Smith, 235–242. London/Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.). Social topics and critique were important for the Cuban novel from the beginning onwards as a means for expressing on the cultural level what was not possible on the political one. The novela de costumbres, describing local customs and expressing civic concerns, was a subgenre suitable to this end. A specifically Cuban topic was the problem of slavery. The economy of the country, characterized above all by sugar mills, coffee plantations, and tobacco farming, depended heavily on it. In the novelas abolicionistas, the system of slavery was documented critically in all of its components.176

221When Mexico was conquered by the Spaniards, it was a region populated by many different indigenous people and dominated by the Aztecs, the mexica, whose capital Tenochtitlan was an urban center reflecting the power and cultural development of their civilization. Before, the Maya had had their flowering period in the southern areas of today’s Mexico. The colonial era was characterized by the establishment and maintenance of an administrative system guaranteeing the Spanish hegemony over the vast territory of the viceroyalty of New Spain. This involved missionary work aimed at christianising the indigenous population and also the economic exploitation of the land, especially the mining of silver and agricultural use (Ruhl and Ibarra García 2000, 22–28, 50–55, 66–97Ruhl, Klaus-Jörg, and Laura Ibarra García. 2000. Kleine Geschichte Mexikos. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart. München: C. H. Beck.). After Mexico’s independence in 1821, the country struggled for its political consolidation, with alternating periods of opportunistic, liberal, and conservative government. Together with social and economic problems, the political difficulties culminated in the Mexican Revolution, which broke out in 1910 (Ruhl and Ibarra García 2000, 130–131Ruhl, Klaus-Jörg, and Laura Ibarra García. 2000. Kleine Geschichte Mexikos. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart. München: C. H. Beck.). The process of political emancipation was closely related to the development of a literary self-conception, which was also reflected in the novels written in the nineteenth century, which took up the cultural, social, and political past and present. The novela indigenista contributed to a revaluation of Mexico’s indigenous past. The historical novels served to denounce abuses of the Spanish colonial power and to highlight the merits of heroes of the independence. Furthemore, contemporary history was thematized and judged with partiality. Types and customs of the middle and lower social strata were sketched in novelas de costumbres. Towards the end of the century, in particular, the currents of realism and naturalism influenced the novelistic production (Rössner 2007, 140–148Rössner, Michael. 2007. Lateinamerikanische Literaturgeschichte. 3rd ed. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.).

222As can be seen from the above overviews, the three countries chosen for the corpus and analyses of novels here represent different political, economic, and cultural systems with local historical developments. The kinds of novels written in Argentina, Cuba, and Mexico in the nineteenth century are a result of these varying circumstances, but at the same time, they are an expression of a common cultural-linguistic colonial heritage, emancipatory concerns, and similar literary influences. The analysis of the various subgenres of the novel intends to examine how these references are reflected stylistically in the texts.